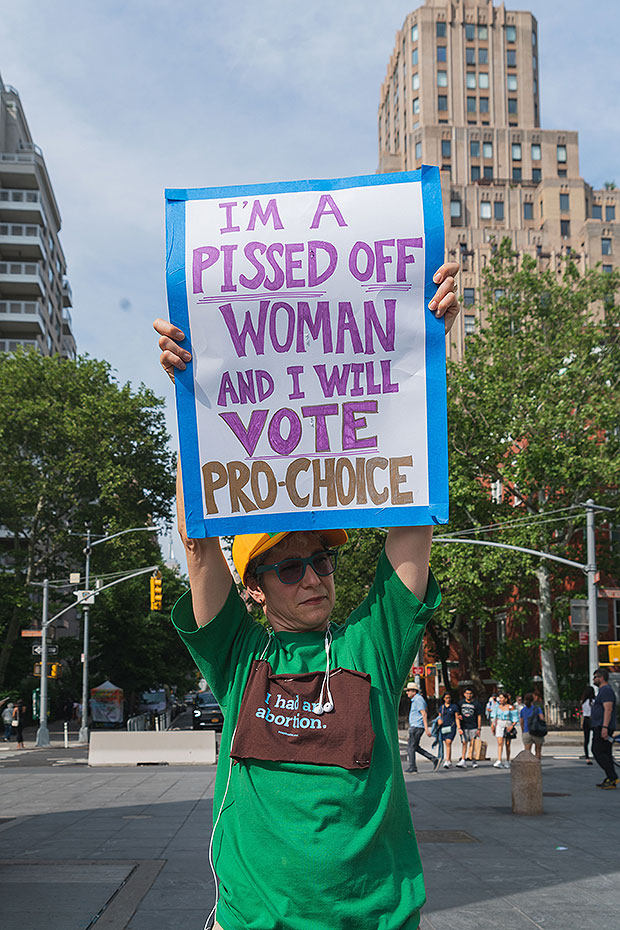

This summer the Supreme Court will likely overturn Roe v. Wade, the 1973 ruling that legalized abortion nationwide, leaving women in as many as 26 states without any option of safe abortion, and filmmakers Emma Pildes and Tia Lessin fear what it will mean for young women in this country. While discussing their new HBO documentary The Janes — a film that shines the light on what women went through to access reproductive care before abortion became legal 50 years ago — Tia told HollywoodLife EXCLUSIVELY, “For want of equitable access to abortion care, women will take matters into their own hands. It’s 2022 so there are some better options, there’s medication abortion, over half of abortions in this country are done by pill. But that needs supervision, and there’s going to be a proliferation of black-market pills. Who knows what women are going to be taking.”

“We know already that maternal mortality will rise for women who are forced to carry children against their will. And, we know from experience, that when abortion is criminalized, it means that women just don’t have access to safe abortion, because women will go to great lengths for bodily autonomy and to make choices about their fate. And if that involves terminating a pregnancy on their own, they will do that, especially young girls,” the Oscar nominated director added.

The Janes tells the story of a group of politically engaged young women who were arrested in Chicago in 1972, after facing off against the police, the mob and the church, to provide an underground safe-haven for illegal abortions. The women, who all called themselves Jane, used code names, blindfolds and safe houses to conceal their identities and their work, and from 1968 until their arrest, they helped facilitate thousands of safe, affordable abortions for women from all walks of life.

The group of mostly white, middle class women were as young as 19 when they started the clandestine network and the film’s director Emma explained that they felt they had a “moral obligation, a philosophical obligation to disrespect a law that disrespects women.” It was this conviction, said the Emmy-nominated director, that allowed the young women to transcend the very real dangers they were up against. “All that riff-raff was something that they just had to make their way through, or try to forget about, because that that wasn’t the point. The point was that women were dying, so they were saving lives.”

With harrowing first person accounts of abortions performed by mobsters, doctors who demanded sexual favors in exchange for terminating a pregnancy, and women who died in septic abortion wards across the country, The Janes offers a brutal look at what young women in America could soon face. A reality that is more than “upsetting” for the women of The Janes, Emma shared. “I can’t imagine what it feels like, having gone through what they went through, laid it out on the line and to have thought that they had sort of done something and made progress and we were out of out of the woods and to be thrown back in, the almost humiliating experience of being manhandled and thrown back in, 50 years later, I can’t imagine how upsetting that must feel to them, in their hearts.”

But, in spite of the film’s heartbreaking subject matter, The Janes is a highly watchable film. “Documentaries can be really heavy, they can be like taking medicine, and that was the opposite of what Emma and I wanted to do,” Tia shared. “We wanted to bring this to life and build the drama, the natural drama, in whatever way we could to tell this really compelling story. We want to emphasize that this is a very watchable film, it’s a thriller.”